This is the unlikely story of 21 ministers and prime ministers who have crossed or are crossing the french Fifth Republic today. Twenty-one politicians who, from one day to the next, find themselves at the head of a ministry by the grace of a President of the Republic and his Prime Minister. The formation of the government, conflicts of attribution, reshuffles, rumours of appointments, evictions, casting errors: it is all the capricious backstage of the games of power examined here under the angle of confidence and which sheds light on the prestigious but unknown function of minister. An original and instructive political saga on the reality of those who hold or have held this prestigious position.

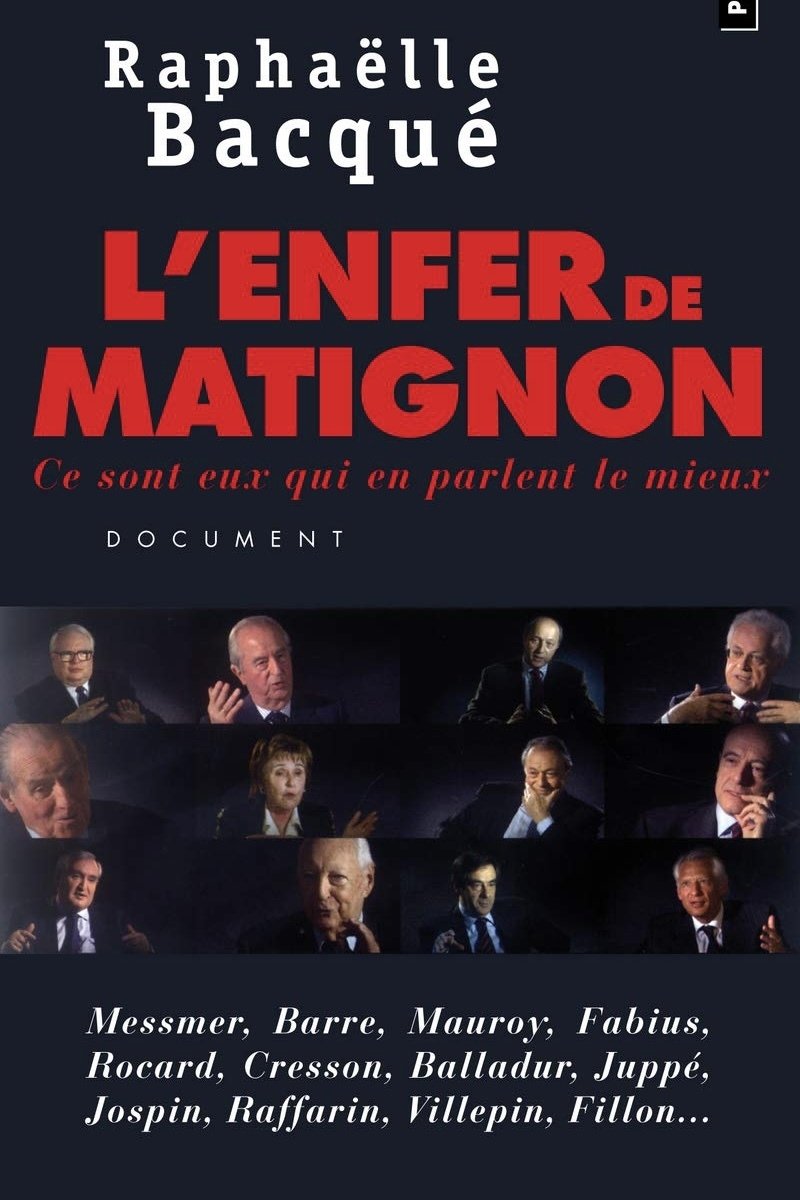

In a series of long interviews, 12 prime ministers talk about their experience in the upper echelons of power. The function of prime minister, torn between the president and the parliament, appointed without necessarily being elected but responsible for everything, is at the center of debate. With the exception of Jacques Chirac (1974-1976 and 1986-1988), deliberately left out because of his image as French President, those who governed France for the past 35 years agreed to discuss the exercise of power, as seen through archive footage, but also how they experienced it personally. Filmed in the same studio and sitting in the same chair, 12 French prime ministers talk freely about their time in office, from their appointment until their resignation.

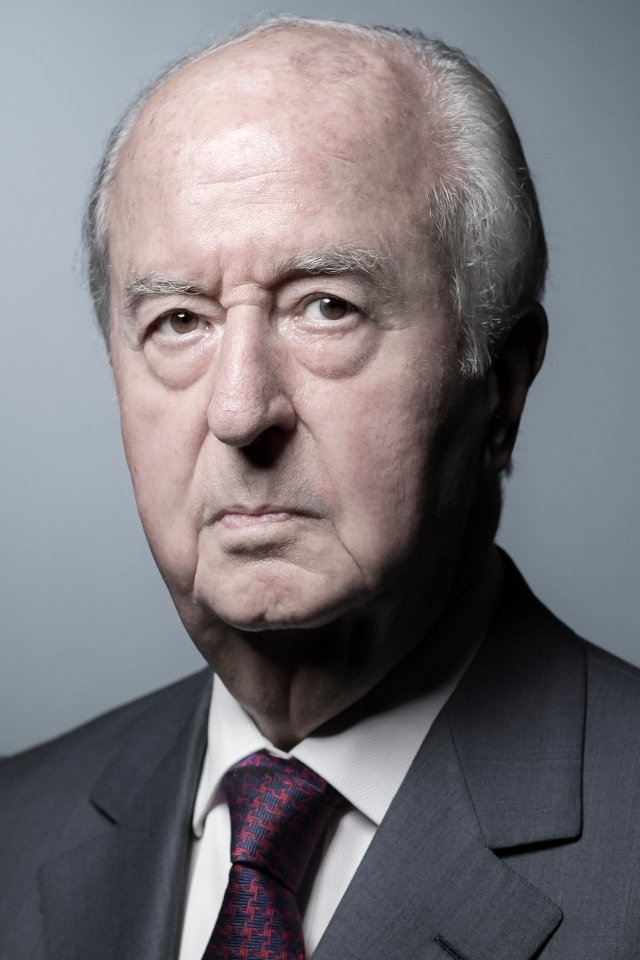

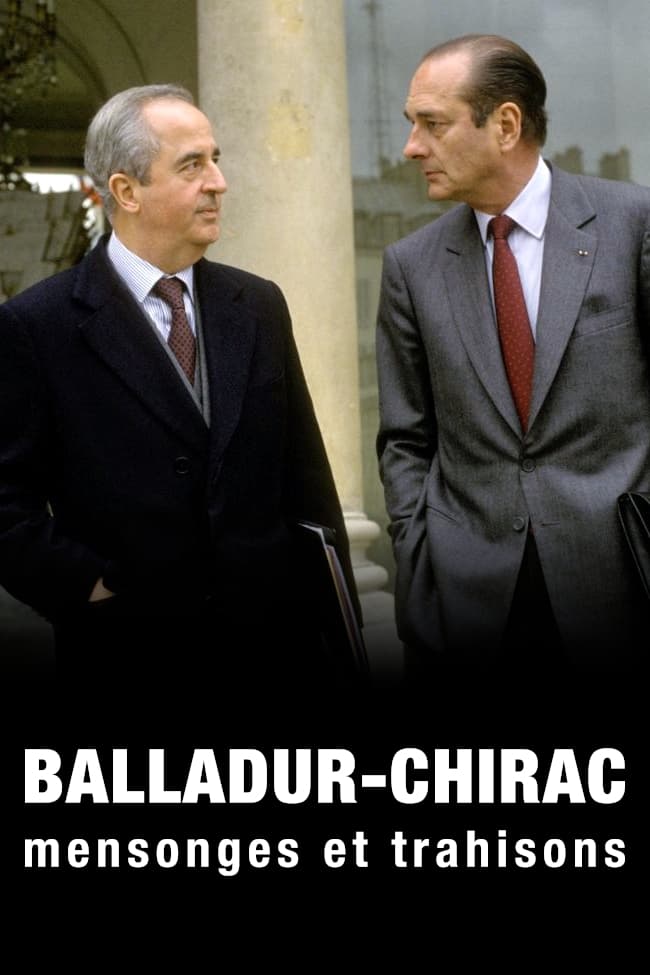

Édouard Balladur (born 2 May 1929) is a French politician who served as Prime Minister of France under François Mitterrand from 29 March 1993 to 17 May 1995. He unsuccessfully ran for president in the 1995 French presidential election, coming in third place. Balladur was born in Izmir, Turkey, to an ethnic Armenian family with five children and longstanding ties to France. His family emigrated to Marseille in the mid-to-late 1930s. In 1957, Balladur married Marie-Josèphe Delacour, with whom he had four sons. Balladur started his political career in 1964 as an advisor to Prime Minister Georges Pompidou. After Pompidou's election as President of France in 1969, Balladur was appointed under-secretary general of the presidency then secretary general from 1973 to Pompidou's death in 1974. He returned to politics in the 1980s as a supporter of Jacques Chirac. A member of the Neo-Gaullist Rally for the Republic (RPR) party, he was the theoretician behind the "cohabitation government" from 1986 to 1988, explaining that if the right won the legislative election, it could govern with Chirac as prime minister without Socialist Party President François Mitterrand's resignation. As Minister of Economy and Finance, he implemented a liberal economic policy reminiscent of the one attributed to Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. He thus implemented a major privatisation programme, involving several companies nationalised in 1945 and 1982, such as the Compagnie Financière de Suez, Paribas and the Société Générale. He also privatised TF1. He also reduced the number of civil servants and state expenditure. Balladur appeared as an unofficial deputy Prime Minister in the cabinet led by Chirac. He took a major part in the adoption of liberal and pro-European policies by Chirac and the RPR. After Chirac's defeat at the 1988 presidential election, part of the RPR held him responsible of the abandonment of Gaullist doctrine, but he kept the confidence of Chirac. When the RPR/UDF coalition won the 1993 legislative election, Chirac declined to become Prime Minister again in a second "cohabitation" with President Mitterrand, and Balladur became Prime Minister. He was faced with a difficult economic situation, but he did not want to make the political errors of the previous cohabitation government. He continued the economic policy he had undertaken in 1986 by carrying out new privatisations (notably Rhône-Poulenc, Banque Nationale de Paris and Elf). Conveying the image of a quiet conservative, he did not question the wealth tax (reestablished by the Socialists in 1988). He disagreed with François Mitterrand by considering that nuclear tests were necessary to maintain the credibility of the French deterrent. Despite corruption affairs affecting some of his ministers, who he forced to resign (thus lending his name to the so-called "Balladur jurisprudence"), he had the support of influential media. ... Source: Article "Édouard Balladur" from Wikipedia in English, licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0.

By browsing this website, you accept our cookies policy.